More or less the same steps for closure are carried out whether the incision is midline or transverse. If the peritoneum and linea alba fascia are separate, the fascial edge may be grasped with toothed forceps (Figure 9) exposing the edge of the peritoneum, which is grasped with Kocher clamps. The closure sutures may be absorbable or nonabsorbable. The technique may use interrupted or continuous sutures that approximate the peritoneum and linea alba either as separate layers or as a combined unified one. If a continuous suture is used, it is technically easier to close from the lower end of the incision upward, particularly if the surgeon stands on the right side of the patient. The suture is anchored in the peritoneum just below on the end of the incision (Figure 10). The needle is passed through the peritoneum and run superiorly in a continuous manner. A medium-width metal ribbon is often placed beneath the peritoneum to insure a clear zone for suturing and to avoid incorporation of visceral or other structures into the suture line. The placement of the continuous suture is made easier if the assistant crisscrosses the two leading Kochers (Figure 11) to approximate the peritoneum. At the superior end of the incision, the looped and free ends of the suture are knotted together across the line of incision (Figure 12). The type of knot and the number of throws are determined by the characteristics of the suture material.

The linea alba fascia may be closed beginning at either end of the incision. Simple interrupted sutures may be placed (Figure 13) or figure-of-eight sutures (see Figure 19) may be used. The sutures are placed about 1 to 2 cm apart whether interrupted or continuous (Figure 14) technique is used.

Alternatively, the linea alba and peritoneum may be closed as a single unified layer with either interrupted or continuous suture. The most expeditious closure may be made with a heavy looped suture on a single needle. The suture material may be either synthetic absorbable or a nonabsorbable in a 0 or #1 size. The suture begins with the transverse placement through the peritoneum and fascia across the lower end of the incision (Figure 15). The needle is then brought through the eye of the loop (Figure 16). Upon tightening, the suture is secured without the need of tying of a knot.

The double loop suture is run in a continuous manner taking full thickness of the linea alba fascia and peritoneum on either side of the incision (Figure 17). After placement of the final stitch superiorly, the needle is cut off and one limb of the suture retracted back across the incision. This allows the two cut ends to be tied along one side of the incision.

Some surgeons prefer to use the figure-of-eight or so-called eight-pound stitch when closing fascia with the interrupted sutures. A full-thickness horizontal bite is taken that enters the linea alba on the far side at A and exits at B (Figure 18). The suture is advanced for a centimeter or two and an additional transverse full-thickness bite is taken that enters at C and exits at D. When the two ends of the suture are tied, a crisscrossing, horizontal figure-of-eight is created (Figure 19). The knot should be tied to one side. In general, the figure-of-eight suture is placed snugly rather than tightly where it may cut through the tissue with any postoperative swelling.

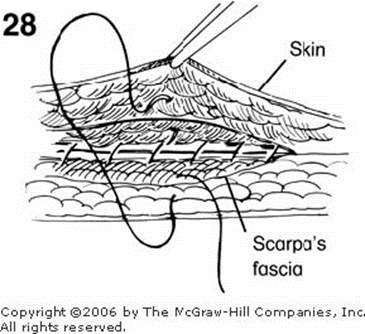

After each knot is tied during the closure, the ends of the suture are held under tension by the assistant and are cut. Silk sutures may be cut within 2 mm of the knot whereas many absorbable or synthetic sutures require several millimeters be left, as the knots may slip. As the suture is held nearly perpendicular to the incision by the assistant, the scissors are slid down to the knot and rotated a quarter turn (Figures 20 and 21). Closure of the scissors at this level allows the suture to be cut near the knot without destroying it. In general, the scissors are only opened slightly such that the cutting occurs near the tips. Additional fine control of the scissors may be obtained by supporting the mid portion of the scissor on the outstretched index and middle fingers of the opposite hand just as the rest supports the chisel on a wood-turning lathe. Following closure of the fascia, some surgeons reapproximate Scarpa's fascia with a few interrupted 3/0 absorbable sutures (Figure 22), whereas others proceed directly to skin closure, the details of which are shown in Figures 28 through 40.

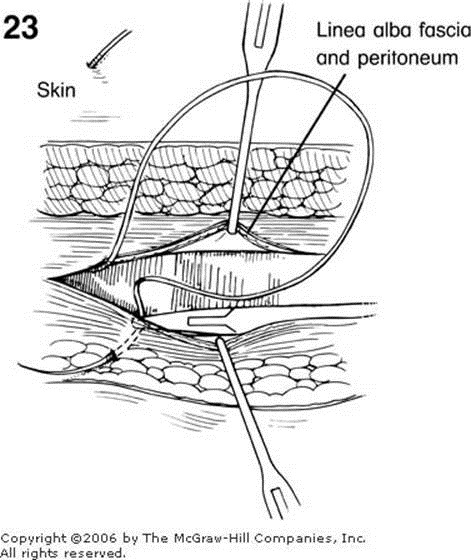

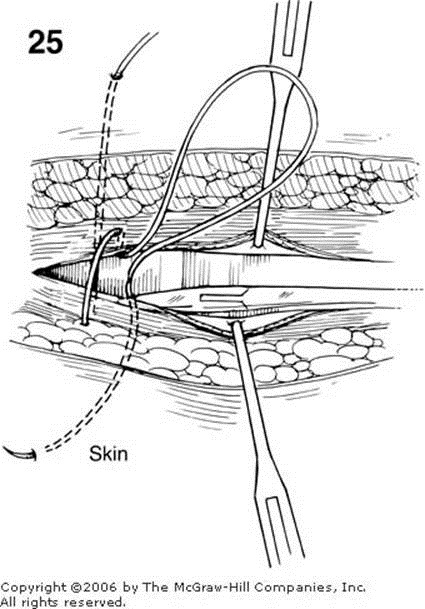

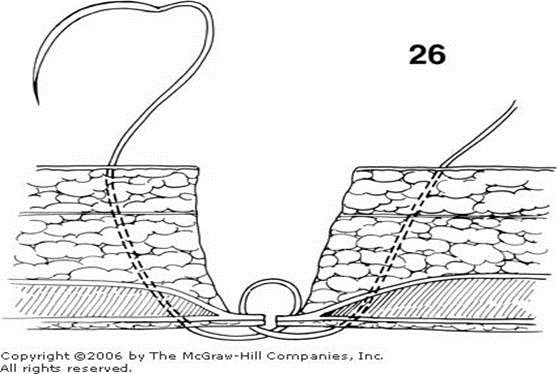

Occasionally, it is necessary to use a retention or through-and-through suture. This is especially true in debilitated patients who have risk factors for dehiscence such as advanced age, malnutrition, malignancy, or contaminated wounds. The most frequent use of retention sutures, however, is for a secondary reclosure of a postoperative evisceration or full-thickness disruption of the abdominal wall. Through-and-through #2 nonabsorbable sutures on very large needles may be placed through all layers of the abdominal wall as a simple suture or as a far-near/near-far stitch (Figure 27). In this technique, the fascia is grasped with Kochers and a metal ribbon retractor is used to protect the viscera. The surgeon places the first suture full thickness through the far side abdominal wall. The needle is then brought through the near linea alba or fascia about one centimeter back from the cut edge with the path going from peritoneal surface towards the skin (Figure 23). The suture then crosses the midline to penetrate far side fascia in a superficial to deep manner (Figure 24). The free intraperitoneal suture is then continued full thickness through the near abdominal wall (Figures 25 and 26). As seen in cross section, it is important that the abdominal wall full-thickness bites taken at the beginning and end of this placement are not positioned so laterally as to include the epigastric vessels within the rectus abdominis muscles. Compression of these vessels when the suture is tied may lead to abdominal wall necrosis. Additionally, the intraperitoneal exposure of this suture should be small so as to minimize the possibility of a loop of intestine becoming entrapped when the retention is tied. In general, the entrance and exit sites are approximately 1½ or 2 in. back from the cut edge of the skin (Figure 27). Many surgeons use retention sutures bolsters or simple 2-in. sections of sterilized red rubber tubing in order to minimize the cutting of the suture into the skin during the inevitable postoperative swelling. Because of this swelling, the retention sutures should be tied loosely rather than snugly such that the surgeon can still pass his or her finger between the retention suture and the skin of the abdominal wall.

Following closure of the peritoneum and the linea alba, Scarpa's fascia may be approximated with 3/0 absorbable suture. Many feel this lessens the subcutaneous dead space within the fat (Figure 28). In thin patients, this suture may be placed in an inverted manner (as shown), with the knot at the bottom of the loop. However, in most patients these sutures are placed upright with the knot on top.

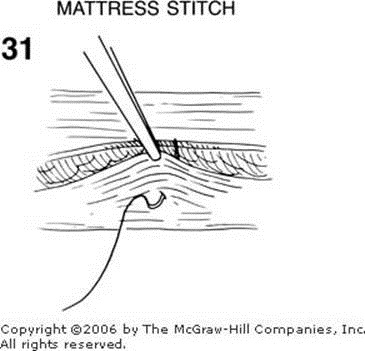

The skin may be closed with interrupted fine 3/0 or 4/0 nonabsorbable sutures using a curved cutting needle (Figure 29). The skin edge is elevated with forceps in such a manner that the needle is introduced perpendicular to the skin on the one side and exits perpendicularly on the opposite. The sutures are spaced such that the distance between them is approximately equal to their width. This creates a pleasing uniform pattern. As the individual sutures are tied, the skin will rise, creating a slight ridge. When all sutures are tied, they are held in the surgeon's left hand and then sequentially cut with the scissors (Figure 30). Some surgeons prefer an interrupted vertical mattress suture for skin closure. The vertical mattress suture is especially well suited for circumstances where the skin edges do not lie in level approximation. The skin is grasped with the toothed forceps. A wide lateral base is created as the needle enters the skin about 1 cm or so lateral to the cut edge (Figure 31). The opposite skin edge is then grasped with forceps and the needle brought through in a symmetric manner (Figure 32). A careful approximation of the skin edges at equal levels is accomplished by a returning small bite that is approximately a millimeter or two from the skin edge and only a millimeter or two deep. A symmetric bite on the proximal skin edge completes the stitch (Figure 33). This stitch is tied loosely producing a gentle ridge effect (Figure 34).

The skin may also be closed with interrupted fine 4/0 or 5/0 synthetic absorbable subcuticular sutures. With this method, the suture must lie in the deepest layers of the corium. The skin edge is grasped with toothed forceps and the suture is placed by either the continuous or interrupted horizontal mattress technique. Multiple interrupted sutures are preferred for short incisions, whereas the continuous one is more suitable for incisions that are more than a few centimeters long. In this technique, small horizontal bites are taken in opposite sides of the skin margins (Figures 35 and 36). When the knot is tied, a perfect approximation occurs (Figure 37). After tying, the sutures are cut as close to the knot as possible. Thereafter, the skin is cleaned of the preparative antiseptic solution and a benzoin-like skin protector is applied. When this becomes tacky, porous adhesive paper tapes are applied transversely (Figure 38). This relieves tension in the incision and provides a simple covering.

Conversely, some surgeons use metal staples for skin closure. Their advantage is speed of application (Figure 39) and ease of removal (Figure 40). Special care must be taken, however, to approximate carefully the everted skin margins with a pair of fine-toothed forceps. The stapling instrument should not press into the skin. A gentle light application will result in the desired mounding up that keeps the two skin edges in good approximation. Some prefer to place these staples widely and use the adhesive paper tapes between them. Finally, a covering gauze dressing is necessary so as to absorb the small amount of serum and blood that evacuates in the postoperative period. In general, staples should be removed sooner rather than later as they penetrate the skin and can result in localized inflammations.

![clip_image012[1] clip_image012[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhjtl6lC5A_fu3C-4FTJlxqKkjgaeorwYb4cO2jz2TaoVd-YdoGBh12jxBpCSAO2TprV0mu8KQ16t09N9sKGr1mWG1V4SzISPmMZgGIWG8UhoQgIK5hzPloXd9Hld86BzwFQeiWpnCN7Fw/?imgmax=800)