Bilateral resection of segments of the vagus nerves in the region of the lower esophagus is a key component in treating intractable duodenal or gastrojejunal ulcers. The motor paralysis and resultant gastric retention that follow truncal vagotomy alone make it mandatory that a concomitant gastric resection or drainage procedure, such as pyloroplasty or an antrally placed gastroenterostomy, be performed. Gastrojejunal or stomal ulcers following a previous gastrectomy or gastrojejunostomy show a favorable response to vagotomy. The use of vagotomy to control the cephalic phase of secretion is preferred when it is desirable to retain as much gastric capacity as possible because of the preoperative nutritional status of the patient with duodenal ulcer. In females and in those individuals below their ideal weight preoperatively, controlling the acid factor by vagotomy followed by pyloroplasty, posterior gastroenterostomy, or hemigastrectomy should be seriously considered. Controlling the acid factor by vagotomy has been used in combination with other procedures in managing chronic recurrent pancreatitis. Serum gastrin levels should be determined.

There are two vagal trunks—the anterior or left vagus nerve, which lies along the anterior wall of the esophagus, and the posterior or right vagus nerve, which is sometimes overlooked since it is more easily separated from the esophagus. The vagus nerves may be divided 5 to 7 cm above the esophageal junction (truncal vagotomy), divided below the celiac and hepatic branches (selective vagotomy), or divided so that only the branches to the upper two-thirds of the stomach are interrupted, while the nerves of Latarjet, innervating the antrum or lower one-third, as well as the celiac and hepatic branches, are retained (proximal gastric vagotomy).

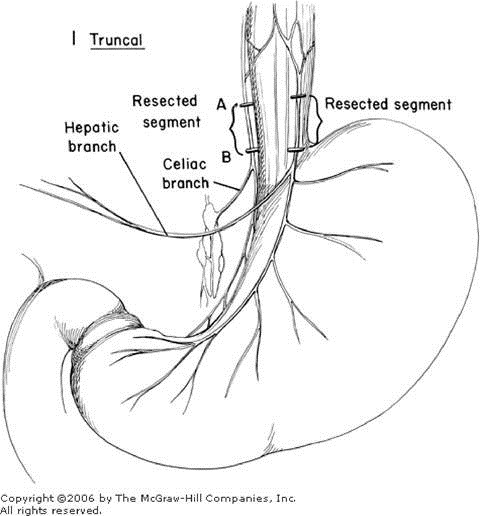

Truncal Vagotomy

A good exposure of the lower end of the esophagus is essential and sometimes requires removal of the xiphoid as well as mobilization of the left lobe of the liver. The vagal nerves should be identified and divided as far from the esophagogastric junction as possible (Figure 1). Sections of these trunks should be sent to the pathologist for microscopic evidence that at least two vagus nerves have been divided. Whether silver clips or ligatures are applied to both ends of each nerve is the choice of the individual surgeon. It may be advisable to ligate the posterior nerve to control possible oozing that may take place in the mediastinum. The esophagus should be carefully inspected, and the area behind the esophagus in particular should be searched as the esophagus is retracted upward to make sure that the posterior vagus nerve is not overlooked. In most instances the cephalic phase of secretion will not be controlled if vagotomy has been incomplete. Some prefer to combine the vagotomy with a hemigastrectomy in order to control the gastric phase of secretion as well as the cephalic phase. Drainage of the antrum is essential by pyloroplasty, gastroenterostomy, or gastroduodenostomy (See Pyloroplasty—Gastroduodenostomy). The increased incidence of recurrent ulceration following vagotomy and antral drainage by pyloroplasty or gastroenterostomy must be weighed against a somewhat higher mortality following vagotomy and hemigastrectomy.

Selective Vagotomy

Selective vagotomy has been suggested as a means of decreasing the incidence of dumping by maintaining the vagal innervation of the liver and small intestine. The vagus nerves are carefully isolated from the esophagus and divided beyond the point where they give off branches to the liver and to the celiac ganglion (Figure 2). It is necessary to visualize clearly the lower end of the esophagus and to follow the anterior nerve down over the esophagogastric junction with identification of the hepatic branch. The nerve is divided beyond the hepatic branch, as shown in Figure 2. The posterior vagus nerve is likewise very carefully identified as it courses down over the esophagogastric junction, and the branch going to the celiac ganglion is identified. The nerve is divided beyond that point in order to make certain that the vagus nerve supply to the small intestine has not been interrupted. Following this, some type of decompression procedure or resection is done.

Proximal Gastric Vagotomy

Proximal gastric vagotomy, also known as highly selective vagotomy, selective proximal vagotomy, or parietal cell vagotomy, is illustrated in Figure 3. This procedure attempts to control the cephalic phase of secretion while maintaining the celiac branch, the hepatic branch, and the anterior and posterior nerves of Latarjet to the distal antrum (Figure 3). In this procedure the vagal denervation is confined to the upper two-thirds of the stomach, while innervation is left intact to the lower third as well as to the biliary tract and small intestine. With superselective vagotomy it is anticipated that a drainage procedure will not be required, since the pyloric sphincter retains its normal function. As a result, the incidence of disagreeable side effects associated with dumping should be decreased.

It has been pointed out that the nerves of Latarjet send out branches in a crow's-foot pattern over the terminal 6 or 7 cm of the antrum. All other branches of the vagus nerves on either side of the lesser curvature are divided up to and around the esophagus (Figure 3). This may be a timeconsuming and difficult technical procedure, particularly when the exposure is limited and the patient obese. Some prefer to identify the anterior and posterior vagus nerves at the lower end of the esophagus and place them under traction with carefully placed sutures or nerve hooks that serve as retractors, thus ensuring that the vagal nerve trunks will not be damaged and at the same time helping define the branches going to the stomach. The dissection is usually started about 6 cm from the pylorus on the anterior wall of the stomach (Figure 4A). Small hemostats are used in pairs to carefully clamp and divide the blood vessels and vagal branches as the dissection progresses up the anterior surface of the gastric wall along the lesser curvature (Figure 4B).

Special care must be taken as the dissection reaches the area where the left gastric artery reaches the lesser curvature of the stomach. The anterior nerve of Latarjet must be identified frequently as the dissection approaches the esophagogastric junction. The peritoneum over the lower end of the esophagus is divided carefully to permit identification of the vagal branches as the dissection is carried around the anterior portion of the esophagogastric junction. Finger dissection may be used to push gently both the anterior as well as the posterior vagus nerves away from the esophageal wall. After the finger has encircled the esophagus, a rubber tissue drain or a rubber catheter is introduced around the esophagus to provide traction. Upward traction on the esophagus provides easier identification of the top branches of the posterior nerve of Latarjet as they course over to the lesser curvature to provide innervation to the posterior gastric wall (Figure 5). The lower 5 cm of the esophagus should be completely cleared to avoid overlooking small fibers. The posterior branches are carefully identified and divided between pairs of small curved hemostats, similar to the procedure utilized on the anterior wall. A rubber tissue drain can be passed around the mobilized lesser omentum, including the nerves of Latarjet, to provide better exposure of the divided lesser curvature. A final search is made for any overlooked vagal branches, incomplete hemostasis, or possible injury to the nerves of Latarjet. Some prefer to peritonealize the lesser curvature by approximating the anterior and posterior gastric walls with a series of interrupted sutures. This approximation ensures control of any small bleeding points and provides insurance against possible necrosis with perforation along the denuded lesser curvature. Since the innervation to the antrum is retained, it is unnecessary to provide antral drainage by either pyloroplasty or gastroenterostomy, provided the duodenal outlet is not obstructed by scarring or a marked inflammatory reaction.

Copyright ©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Privacy Notice. Any use is subject to the Terms of Use and Notice. Additional Credits and Copyright Information.