INDICATIONS

The Billroth I procedure for gastroduodenostomy is the most physiologic type of gastric resection, since it restores normal continuity. Although long preferred by some in the treatment of gastric ulcer or antral carcinoma, its use for duodenal ulcer has been less popular. Control of the acid factor by vagotomy and antrectomy has permitted retention of approximately 50 percent of the stomach while ensuring the lowest ulcer recurrence rate of all procedures (Figure 1). This allows an easy anastomosis without tension, providing both stomach and duodenum have been thoroughly mobilized. Furthermore, the poorly nourished patient, especially the female, has an adequate gastric capacity for maintaining a proper nutritional status postoperatively. Purposeful constriction of the gastric outlet to the size of the pylorus tends to delay gastric emptying and decrease postgastrectomy complaints. Gastrin levels are determined.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The patient's eating habits should be evaluated, and the relationship between his or her preoperative and ideal weight should be determined. The retention of an adequate gastric capacity as well as reestablishment of a normal continuity tends to give the best assurance of a satisfactory nutritional status in undernourished patients, especially females.

ANESTHESIA

General anesthesia via an endotracheal tube is used rather routinely.

POSITION

The patient is laid supine on the flat table, the legs being slightly lower than the head. If the stomach is high, a more erect position is preferable.

OPERATIVE PREPARATION

The skin is prepared in a routine manner.

INCISION AND EXPOSURE

A midline or left paramedian incision is usually made. If the distance between the xiphoid and the umbilicus is relatively short, or if the xiphoid is quite long and pronounced, the xiphoid is excised. Troublesome bleeding in the xiphocostal angle on either side will require transfixing sutures of fine silk and bone wax applied to the end of the sternum. Sufficient room must be provided to extend the incision up over the surface of the liver, because vagotomy is routinely performed with hemigastrectomy and the Billroth I type of anastomosis, especially in the presence of duodenal ulcer.

DETAILS OF PROCEDURE

The Billroth I procedure requires extensive mobilization of the gastric pouch as well as the duodenum. This mobilization should include an extensive Kocher maneuver for mobilization of the duodenum. In addition, the greater omentum should be detached from the transverse colon, including the region of the flexures. In many instances the splenorenal ligament is divided, as well as the attachments between the fundus of the stomach and the diaphragm. Additional mobility is gained following the division of the vagus nerves and the uppermost portion of the gastrohepatic ligament. The stomach is mobilized so that it can be readily divided at its midpoint. The halfway point can be estimated by selecting a point on the greater curvature where the left gastroepiploic artery most nearly approximates the greater curvature wall (Figure 1). The stomach on the lesser curvature is divided just distal to the third prominent vein on the lesser curvature.

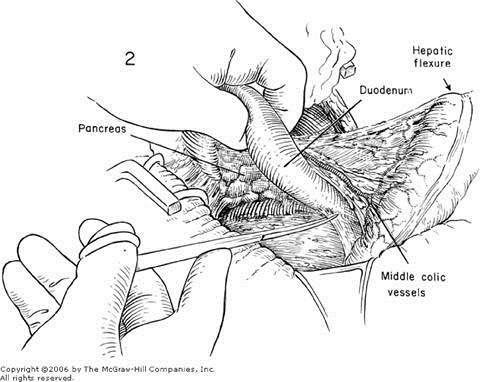

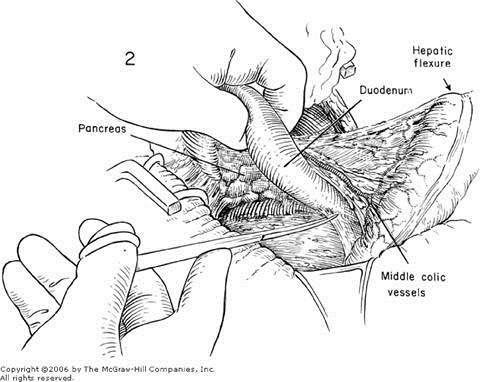

Extensive mobilization of the duodenum is essential in the performance of the Billroth I procedure. Should there be a marked inflammatory reaction, especially in the region of the common duct, a more conservative procedure, such as a pyloroplasty or gastroenterostomy and vagotomy, should be considered. If it appears that the duodenum, especially in the region of the ulcer, can be well mobilized, the peritoneum is incised along the lateral border of the duodenum and the Kocher maneuver is carried out. Usually it is unnecessary to ligate any bleeding points in this peritoneal reflection. With blunt finger and gauze dissection the peritoneum can be swept away from the duodenal surface as the duodenum is grasped in the left hand and reflected medially (Figure 2). It is important to remember that the middle colic vessels tend to course over the second part of the duodenum and are many times encountered rather suddenly and unexpectedly. For this reason the hepatic flexure of the colon should be directed downward and medially and the middle colic vessels identified early (Figure 2). As the posterior wall of the duodenum and head of the pancreas are exposed, the inferior vena cava readily comes into view. The firm, white, avascular ligamentous attachments between the second and third parts of the duodenum and the posterior parietal wall are divided with curved scissors, down through and almost including the region of the ligament of Treitz (Figure 2). Thisextensive mobilization is carried downward in order to ensure a very thorough mobilization of the duodenum. Following this, the omentum is separated from the colon, as described in Gastrectomy, Subtotal—Omentectomy. In obese patients it is usually much easier to start the mobilization by dividing the attachment between the splenic flexure of the colon and the parietes (Figure 3). An incision is made along the superior surface of the splenic flexure of the colon as the next step in freeing up the omentum. This should be done in an avascular cleavage plane. The lesser sac is entered from the left side. Care should be taken not to apply undue traction upon the tissues extending up to the spleen, since the splenic capsule may be torn, and troublesome bleeding, even to the point of requiring splenectomy, may be encountered.

The omentum is then dissected free throughout the course of the transverse colon.

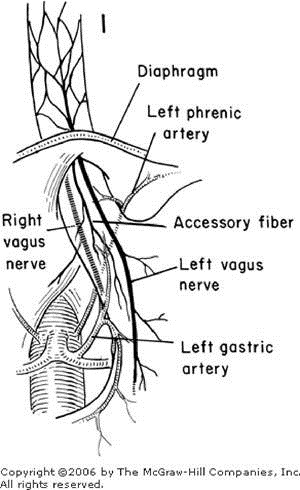

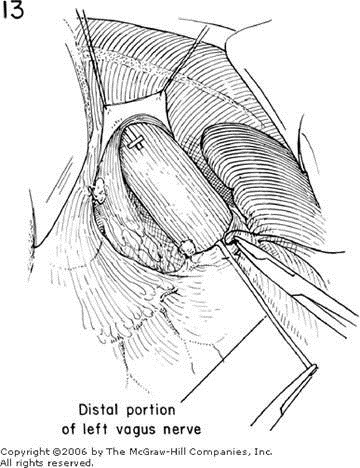

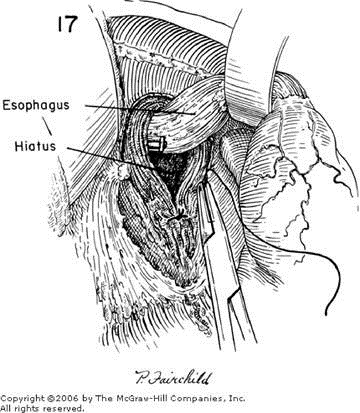

The left lobe of the liver is then mobilized, and a vagotomy carried out as described in Vagotomy, Subdiaphragmatic Approach, Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. At this point considerable distance can be gained if the peritoneum attaching the fundus of the stomach to the base of the diaphragm is divided up to and around the superior aspect of the spleen. If the exposure appears difficult, it is advisable for the surgeon to retract the spleen downward with his right hand and, using long curved scissors in his left hand, divide the avascular splenorenal ligament (see Splenectomy, Figures 5 and 6). It must be admitted that sometimes troublesome bleeding does occur, which requires an incidental splenectomy, but in general greatmobilization of the stomach is accomplished by this maneuver. Any bleeding from the splenic capsule should be controlled by conservative measures to minimize the need for splenectomy.

So far, the surgeon is not committed to any particular type of gastric resection but has ensured an extensive mobilization of the stomach and duodenum. The omentum should be reflected upward and the posterior wall of the stomach dissected free from the capsule of the pancreas, should any adhesions be found in this area. In the presence of a gastric ulcer, penetration through to the capsule of the pancreas may be encountered. These adhesions can be pinched off between the thumb and index finger of the surgeon and the ulcer crater allowed to remain on the capsule of the pancreas. A biopsy for frozen section study should be taken of any gastric ulcer since malignancy must be ruled out. The colon is returned to the peritoneal cavity. The right gastric and gastroepiploic arteries are doubly ligated (see Gastrectomy, Subtotal, Figures 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16), and the duodenum distal to the ulcer divided.

At least 1 or 1.5 cm of the superior as well as the inferior margins of the duodenum must be thoroughly cleared of fat and blood vessels adjacent to the Potts vascular clamp in preparation for the angle sutures. This is especially important on the superior side in order to avoid a diverticulum-like extension from the superior surface of the duodenum with an inadequate blood supply for a safe anastomosis. After the duodenal stump has been well prepared for anastomosis, the end that has been closed with the Potts clamp is covered with a moist, sterile gauze while the site of resection of the stomach is decided upon (Figure 4).

In many instances, especially in the obese patient, it is advisable to further mobilize the stomach by dividing the thickened, lowermost portion of the gastrosplenic ligament without dividing the left gastroepiploic vessels. Considerable mobilization of the greater curvature of the stomach without traction on the spleen can be obtained if time is taken to divide carefully the extra heavy layer of adipose tissue that is commonly present in this area. Following this further mobilization of the greater curvature, a point is selected where the left gastroepiploic vessel appears to come nearer the gastric wall. This is the point in the greater curvature selected for the anastomosis, and the omentum is divided up to this point with freeing of the serosa of fat and vessels for the distance of the surgeon's finger (Figure 4). Traction sutures are applied to mark the proposed site of anastomosis. A site on the lesser curvature is selected just distal to the third prominent vein on the lesser curvature (Figure 1). Again, two traction sutures are applied, separated by the width of the surgeon's finger. This distance of about a centimeter on both curvatures assures a good serosal surface for closure of the angles.

It makes little difference how the stomach is divided, although there is some advantage to using a linear stapling instrument. Regardless of the crushing clamp that is to be applied, the curvatures of the stomach should be fixed by the application of Babcock forceps to prevent rotation of the tissues when the clamp is closed. Before the stomach is divided, a row of interrupted 0000 silk sutures may be placed almost through the entire gastric wall in order to (1) control the bleeding from the subsequent cut surface of the gastric wall, (2) fix the mucosa to the seromuscular coat, and (3) pucker and constrict the end of the stomach (Figure 5).

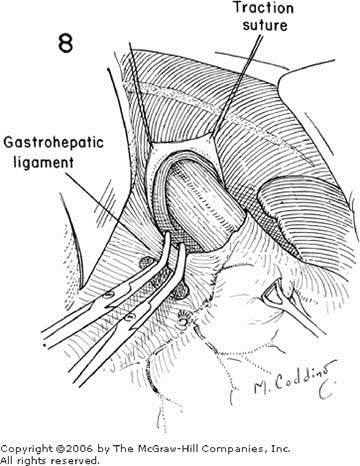

Additional sutures of fine silk are taken around the edge of the mucosal opening until the end of the stomach has been puckered to fit relatively snugly around the surgeon's index finger. This opening should be approximately 2.5 to 3 cm wide (Figure 6). These sutures are then cut in anticipation of a direct end-toend anastomosis with the duodenum (Figure 7). If the margins of the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach as well as the superior and inferior margins of the duodenum have been properly prepared, it is relatively easy to insert angle sutures of 00 silk. Successful closure of the angles depends upon starting the suture on the anterior gastric as well as the anterior duodenal wall rather than more posteriorly. Interrupted sutures of 00 silk are then taken to close the stomach and duodenum together. Slightly bigger bites are necessary on the gastric side as a rule rather than on the duodenal side, depending upon the discrepancy in size between the two openings (Figure 8). The sutures should be tied, starting at the lesser curvature and progressing downward to the greater curvature. The angle sutures are retained while additional 0000 silk or fine absorbable synthetic sutures are placed to approximate the mucosa (Figure 9, A–A' and B–B'). Some prefer a continuous synthetic absorbable suture to approximate the mucosa. No clamps are applied to the stomach or duodenum to control bleeding, since the sutures on the gastric side, if properly placed, should provide complete hemostasis as far as the stomach is concerned. Bleeding from the duodenal side is controlled by placing interrupted 0000 silk sutures. The anterior mucosal layer is closed with a series of interrupted sutures of 0000 silk or a continuous synthetic absorbable suture. The seromuscular coat is then approximated to the duodenal wall with a layer of interrupted mattress sutures (Figure 10). It has been found that a cuff of gastric wall can be brought over the duodenum, resulting in a "pseudo-pylorus," if two bites are taken on the gastric side and one bite on the duodenal side. When this suture is tied (Figure 10), the gastric wall is pulled over the initial mucosal suture line.

The vascular pedicles on the gastric side are anchored to the ligated right gastric pedicle along the top surface of the duodenum as well as the ligated right gastroepiploic artery pedicle (Figure 10, A and B). A and B are then tied together to seal the greater curvature angle (Figure 11). A similar type of approximation is effected along the superior surface in order to seal the angle and remove all tension from the anastomosis (Figure 11). Cushing silver clips placed at the site of anastomosis will aid in identifying this area when future x-rays are obtained. The stoma should admit one finger relatively easily. There should be no tension whatsoever on the suture line.

The upper quadrant is inspected for oozing and thoroughly irrigated with saline.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Two liters of Ringer's lactate are given and the blood volume restored during the first 24 hours. The nasogastric tube is allowed to drain by gravity or is attached to low-pressure suction. Frequent irrigations of the tube with small amounts of saline are necessary to avoid obstruction and resultant gastric distention. Losses from the nasogastric tube are accurately recorded. Daily serum electrolyte levels are determined as long as intravenous fluids are given, and every two to three days thereafter.

When bowel activity has resumed, clear liquids are given by mouth and the nasogastric tube is clamped. Four hours after each of the first several meals the tube is unclamped and gastric residual measured. If there is no evidence of retention, a progressive feeding regimen is begun. This consists of five or six small feedings per day of soft food, moderately restricted in volume, high in protein, and relatively low in carbohydrate. Although many patients after gastric surgery dislike dairy products, the majority will tolerate milk, eggs, custards, toast, and cream soups, as the first step of the diet. Other soft foods are added as rapidly as the tolerance of the individual will permit. By the tenth day, a feeling of fullness may develop caused by mild retention and a tendency to overeat. Self-restriction of the dietary intake for a few days is indicated.

The patient's weight is recorded daily. The progressive regimen forms a basis for the discharge diet. Instructions are given to the patient to eat frequently, avoid concentrated carbohydrates, and to add "new" foods, including spices, and other food restricted preoperatively, one at a time. Eventually, the only limitations to the individual's diet are those imposed by his or her own intolerance.

Intermittent and regular follow-up discussions are essential over a long period of time to answer the many problems encountered by patients before the operation can be considered a complete success. Return to an unlimited diet and maintenance of ideal weight with freedom from gastrointestinal complaints are the goals.

![clip_image002[10] clip_image002[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEghXB_jm3BVY6JUjhipMV3HKElr5xFhG2V0lDlVjR19Xo4yM9XYRj5d9TQ0Z9xaNBo9Obt0Y9agCy9dDxUVs51qjjrn3rL6MYDCt6GJweZAZK4x28rNiM4h-zECx9jCjn4qEODkXoJeoNA/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image004[10] clip_image004[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgaQiQ9-Sh8d8gKXfiuKiXmQGPxXz2ydWSaxfrJqyChsVMcTherdIQuPo0V0-7XUukBhz2WIFR7J_BlfzO0R7KBVL3TZdmzd5VtW_1RVpu89tgXjT62CtxPFNRnf04EQZXMAzUFAoZPP38/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image006[10] clip_image006[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEixn7J-ZjvdCUCY0HP8BygL4fpslj8A71BRiNn0VlyDBRhOA9h3PjMgawLbR_r8itHh4vfNgwJUiH3mfYZ471sb7FVKxW96iC4cpfPSrlrvBP33ue3zQKCZPRTWVfTcJen9xZC7rh-7sNQ/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image008[10] clip_image008[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh4N9v1pWoVICUGFCIPyIdNd9lu8YGv4ro4W9TGA8E3JJVFIoVjffXEmKVHIjgZgw8pW4X2C2gdDW57lsfviGXi_89E6jhYEA3zzXMqu4yiPoWcBASKFobaEkhyphenhyphen1CdKlLTxCXuBXD_IqVs/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image010[10] clip_image010[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEge-1loCe6FnGZJ7OIUHUUB9LH2XMo1DB-MnMqvNCb8IP5pNK6GMQa29cp2K4ZiHhgkhb3H2upzOwmYuTtyZX-D2T2CW_B1UxyNr3olw9gIDnrKBRv452qWbuCKY1n8qdbKjuQd36YeKUE/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image012[10] clip_image012[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKJA3TSmoGEc1ApOnkfEqf8HviNORDDDlhZD5N75w9oypfxsu3PsD08BlYG7jkvx9HDQR3wSOuKxmPdaZepjCtJzgocJ2flKKaVTnT92-OKJ2wzsMGlX5obrLva44XXX6xQzUUBs_GazI/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image014[10] clip_image014[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhUMi_qs7ffDgXFIcCbVEZAhd8jYAuXtYWUovOwrGFILZaMegGmfOZyWC98EurNTno32gEJ8ouKQtj3lSicFnLZzVClGODxcYCp6j9w1CNQ-OKY1Kj2YoJgsb1fhMaUoBmqDQViS2u3EF0/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image016[10] clip_image016[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiTac4P4NlvUnueDDYdts6ywyo031OJKj0ZI07mubC8OkOAxFW8q3kvXGgJZ2R3cXjIkuEAHeF9T5yi1mUPBVtkr-1YRxGmleP8Fx73jURjVOFYX2hRa57VC2Y8GxuXUQMxOFUX4sWtBfk/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image018[10] clip_image018[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj9DxgSfudbtIlzrI40GFTpOKJFBapRIZkO7uZwSuiop1-beZbjDWuzcQpphLV1s4hGqiRiyeawLbBP0xvnLEzC7sJGb3wyQnABbZwdiBc-v-LFapx07FFTK86VA1DB-nB95HmZXAohiaE/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image020[10] clip_image020[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhkmxxK861l8YKC_vD7Posee5ZMLQNb8FlQ5m7pllkBsuDSQMWv73hmZn-DRQGTQL4I6f2K1u1VFNfJYV8CTB4JOMrl9pglmco-DVWSi9vmTP0RSOcNX7kKsv6S6yfYo4yadhS761GOEDI/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image022[10] clip_image022[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKbetIE1KTVRHUPXgA3PkpnthrgDU_X0DqRlnXtRxhcAc-POrb_GW0eWOkNK54mxkk5Ei7TvssQ5k0W14oQ0EsP8cIHk_Hiloi-YREKahK5GfW4Toks_hgBnSrCYavyCKX4bq-BcUDKXw/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image024[11] clip_image024[11]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj2GRKT0ITI23fTWk6PYEAdNhmHqgeixrOzEzrsk4nnhpBRHdPxUk0Y8rHxkLJNG87wNW8CNoYUKpYI1lskcD_jP31lpNpno3G1fKyF8W13mQ7QfZKb991yDi8Q8twpj-iW5P_BafYN93A/?imgmax=800)