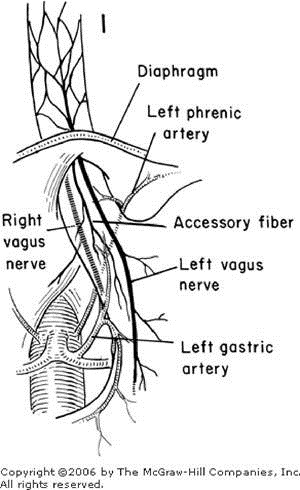

The long-term results of vagotomy are closely related to the completeness of the vagotomy and to efficient drainage or resection of the antrum (see Vagotomy, Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4).

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

A careful evaluation of the adequacy and extent of the medical management is made. Secretion determination with continuous suction may be done to ascertain the gastric secretory status of the patient. Fasting serum gastrin levels are indicated. Proof of the presence of a duodenal ulcer and determination of the amount of gastric retention are established by endoscopy, by a barium meal, by fluoroscopy and roentgenologic studies, and by fasting aspirations through a stomach tube. Constant nasogastric suction is maintained during the operation.

ANESTHESIA

General anesthesia, supplemented with curare for relaxation, is satisfactory. The insertion of an endotracheal tube provides smoother operating conditions for the surgeon and easy control of the airway for the anesthesiologist.

POSITION

The patient is placed flat on the operating table, with the foot of the table lowered to permit the contents of the abdomen to gravitate toward the pelvis.

OPERATIVE PREPARATION

The skin is prepared in the usual manner.

INCISION AND EXPOSURE

A high midline incision is extended up over the xiphoid and down to the region of the umbilicus (Figure 1). In some patients the exposure is greatly enhanced by removal of a long xiphoid process. A thorough exploration of the abdomen is carried out, including visualization of the site of the ulcer. The location of the ulcer, especially if it is near the common duct, the extent of the inflammatory reaction, and the patient's general condition should all be taken into consideration in evaluating the risk of gastric resection in comparison to a more conservative drainage procedure.

The next step is to mobilize the left lobe of the liver. This maneuver is especially useful in obese patients where good exposure enhances the probability of complete vagotomy. If the operator stands on the right side of the patient, it is usually easier to grasp the left lobe of the liver with the right hand and with the index finger to define the limits of the thin, relatively avascular left triangular ligament of the left lobe of the liver. In many instances the tip of the left lobe extends quite far to the left (Figure 2). By downward traction on the left lobe of the liver, and with the index finger beneath the triangular ligament to define its limits and to protect the underlying structures, the triangular ligament is divided with long, curved scissors. The assistant stands on the patient's left side and can usually do this more easily than the surgeon (Figure 3). It should be unnecessary to tie any bleeding points; however, occasionally the tip of the left lobe may require several ties to control slight oozing on the liver side. The left lobe of the liver is then folded either downward or upward so that the region of the esophagus is clearly exposed (Figure 4). A moist, warm gauze pad is placed over the liver, and an S retractor is inserted to maintain even pressure throughout the rest of the procedure (Figure 5). In many instances the exposure is adequate without mobilization of the left lobe of the liver.

DETAILS OF PROCEDURE

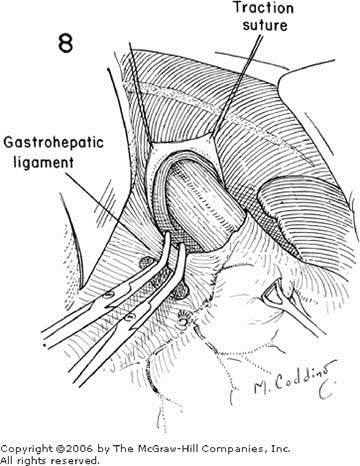

The region of the esophagus is palpated. The peritoneum immediately over the esophagus is grasped with toothed forceps, and an incision is made in the peritoneum at right angles to the long axis of the esophagus (Figure 5). The incision may be extended laterally to ensure mobilization of the fundus of the stomach. Curved scissors are then directed gently upward to free the anterior surface of the esophagus from the surrounding tissue. This can be done by blunt dissection, using the index finger, which has been covered with a piece of gauze (Figure 6). Traction sutures of fine silk may be introduced into this peritoneal cuff to assist in visualizing the area. After 1 in. or more of the anterior wall of the esophagus has been freed from the surrounding structures, the index finger should be introduced beneath the esophagus from the left side. It is frequently necessary to loosen some adhesions in this area by sharp dissection. Usually, little difficulty is encountered in gently passing the index finger beneath the esophagus and its indwelling nasogastric tube and completely freeing it from the surrounding structures. Just to the right of the esophagus, the index finger will usually encounter resistance from the uppermost limit of the hepatogastric ligament (Figure 7). This portion of the structure should be divided, since its division affords more mobilization of the esophagus and tends to provide exposure of the posterior or right vagus nerve. The major portion of the hepatogastric ligament in this area is quite avascular and thin, so that it can be perforated easily with scissors or the index finger. A pair of right-angle clamps is then applied to the uppermost portion of the ligament, and the contents of these clamps divided with long, curved scissors (Figure 8). This exposes the region posterior to the esophagus and ensures adequate exposure of the hiatal region.

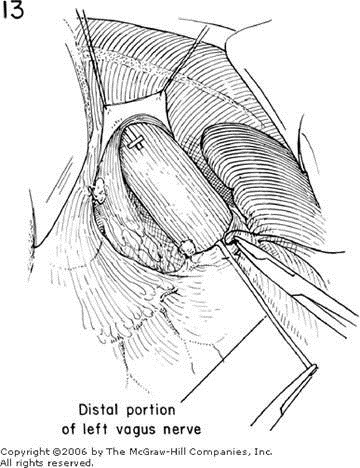

The contents of these clamps are then ligated with 00 silk sutures. Downward traction is maintained on the esophagus while it is further freed from the surrounding structures by blunt dissection with the index finger. The vagus nerves are not always easily identified, but their location is more quickly discovered by palpation (Figure 9). As a tip of the index finger is passed over the esophagus, the tense wirelike structure of the nerve is easily identified. It should be remembered that one or more smaller nerves may be found, both anteriorly and posteriorly, in addition to the large left and right vagus nerves. Additional small filaments may be seen crossing over the surface of the esophagus in its long axis. The left vagus nerve is usually located on the anterior surface of the esophagus, a little to the left of the midline, while the right vagus nerve is usually located a little to the right of the midline, posteriorly (Figures 10 and 10A). The left vagus is then grasped with a blunt nerve hook, such as the de Takats nerve dissector, and with curved scissors is dissected free from the adjacent structures (Figure 11). The nerve can be separated from the esophagus easily by blunt dissection with the surgeon's index finger. It is usually possible to free at least 6 cm of the nerve (Figure 12). The nerve is crimped with a silver/tantalum clip and is divided with long, curved scissors as high as possible. It is unnecessary to ligate the ends of the vagus nerve unless bleeding occurs from the gastric end (Figure 13). The use of silver clips at the point where the vagus nerves divide minimized bleeding and serves to identify the procedures on subsequent roentgenograms. After the left vagus nerve has been resected, the esophagus is rotated slightly, and the traction is directed more to the left. It is usually not difficult to dissect free the right or posterior vagus nerve with the index finger or nerve hook (Figure 14). In some instances it has been found that the nerve has been separated from the esophagus at the time it was initially freed from the surrounding structures. The nerve, in such instances, appears to be resting against the posterior wall of the esophageal hiatus. The tendency to displace the right vagus nerve posteriorly during the blind process of freeing the esophagus no doubt accounts for the fact that this large nerve may be overlooked while all filaments about the esophagus are meticulously divided. This is the nerve most commonly found to be intact at the time of secondary exploration for a clinical failure of the vagotomy. A careful search should be made for additional nerves, since it is not uncommon to find more than one. A minimum of 6 cm of the right or posterior vagus nerve should be resected (Figure 15). Although the nerves may be clearly identified, the surgeon should not be satisfied until another careful search has been made completely around the esophagus. By traction on the esophagus and by direct palpation, any constricting band should be freed and resected, and a careful inspection should be made throughout the circumference of the esophagus. The operator will find that many of the little filaments that he dissects, in the belief that they are nerves, will prove to be small blood vessels that will require ligation. A final survey should always be made to be absolutely certain that the large right vagus nerve has not been displaced posteriorly, thus escaping division. A frozen section examination may be obtained to verify that both nerves have been removed. In order to correct esophageal reflux associated with an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter, some surgeons perform fundoplication around the lower esophagus. The mobilized fundus is approximated by four or five sutures about the lower end of the esophagus with a large stomach tube in place to prevent excessive constriction. (See Fundoplication.)

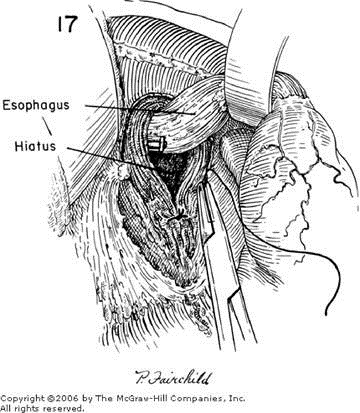

Traction should be released and the esophagus allowed to return to its normal position. The area should be carefully inspected for bleeding. No effort is made to reapproximate the peritoneal cuff over the esophagus to the cuff of peritoneum at the junction of the esophagus with the stomach. Finally, the esophagus is retracted upward and to the left by a narrow S retractor in order to expose the crus of the diaphragm. Two to three sutures of No. 1 silk may be placed to approximate the crus of the diaphragm as in the repair of a hiatus hernia if the hiatus appears patulous (Figures 16 and 17). Sufficient space about the esophagus must be retained to admit one finger or the passage of a 54 French or larger esophageal dilator into the stomach. All packs are removed from the abdomen, and the left lobe of the liver is returned to its normal position. It is not necessary to reapproximate the triangular ligament of the left lobe.

Vagotomy must always be accompanied either by a gastric resection or a drainage of the antrum by posterior gastroenterostomy or division of the pylorus by pyloroplasty. Since gastric emptying may be unduly delayed following vagotomy, efficient gastric drainage by gastrostomy should be considered.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Constant gastric suction is maintained for a few days until it has been determined that the stomach is emptying satisfactorily. If evidence of gastric dilatation develops, constant gastric suction is instituted. Occasionally, a moderate diarrhea will develop, which may be temporarily troublesome. The general care is that of any major upper abdominal procedure. Inability to swallow solid food because of temporary cardiospasm may occur for a few days in the early postoperative period. Six small feedings consistent with an ulcer diet should be recommended in order to combat the distention that may occur with an atonic stomach. Sweet juice, as well as hot and cold liquids, should be avoided, especially at breakfast. Smoking and coffee or tea consumption should be minimized until the patient is symptom-free and ideal weight is attained. The return to an unrestricted diet is determined by the patient's progress.

Copyright ©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Privacy Notice. Any use is subject to the Terms of Use and Notice. Additional Credits and Copyright Information.