PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The patient is carefully positioned on the operating table while taking into consideration the need for special equipment such as heating pads, electrocautery grounding plates, sequential compression stockings, and anesthesia monitoring devices. The arms may be positioned at the side or at right angles on arm boards, which allows the anesthesiologist better access to intravenous lines and other monitoring devices. It is important that the patient be positioned without pressure over the elbows, heels, or other bony prominences; neither should the shoulders be stretched in hyperabduction. The arms, upper chest, and legs are covered with a thermal blanket. Simple cloth loop restraints may be placed loosely about the wrists, whereas a safety belt is usually passed over the thighs and around the operating table. The entire abdomen is shaved, as is the lower chest when an upper abdominal procedure is planned. In hirsute individuals, the thigh may also require simple shaving for effective application of an electrocautery grounding pad. The grounding pad should not be placed in the region of metal orthopedic implants or cardiac pacemakers. Loose hair may be picked up with adhesive tape and the umbilicus may require cleaning out with a cotton-tipped applicator. The first assistant scrubs, puts on sterile gloves, and then places sterile towels well beyond the upper and lower limits of the operative field so as to wall off the unsterile areas. The assistant vigorously cleanses the abdominal field with gauze sponges saturated with antiseptic solution (see Surgical Technique). Some prefer iodinated solution for skin preparation.

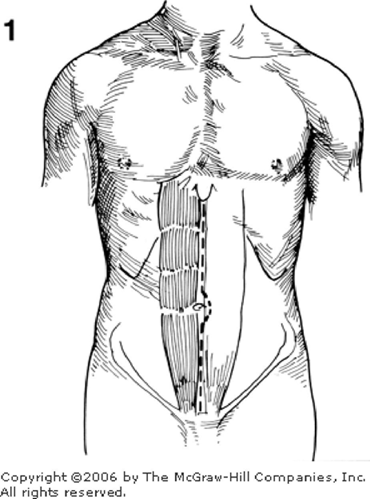

The incision should be carefully planned before the anatomic landmarks are hidden by the sterile drapes. Although cosmetic considerations may dictate placing the incision in the lines of skin cleavage (Langer's lines) in an effort to minimize subsequent scar, other factors are of greater importance. The incision should be varied to fit the anatomic contour of the patient. It must provide maximum exposure for the technical procedure and of the anticipated pathology while creating minimal injury to the abdominal wall, especially in the presence of one or more scars from previous surgical procedures. The most commonly used incision is a midline one that goes between the two rectus abdominis muscles, around the umbilicus, and through the linea alba (Figure 1). For procedures in the pelvis, the incision is extended to the pubis; whereas for upper abdominal operations, the incision may extend up and over the xiphoid. Following preparation, the abdomen is walled off with sterile towels placed transversely at the xiphoid and pubis and longitudinally about either rectus muscle. Some surgeons prefer to further seal the field with an adhesive plastic drape that may be impregnated with an antiseptic solution. This technique is particularly useful in patients who have pre-existing intestinal stomas, tubes, or other processes that may contaminate the operative field.

INCISION AND EXPOSURE

In making the incision, the operator should hold the scalpel with the thumb on one side and the fingers on the other. The distal portion of the handle rests against the ulnar aspect of the palm. Some prefer to rest the index finger on top of the knife handle as a sensitive means of guiding the pressure being applied to the blade. The primary incision may be made in three ways. First, the surgeon may take a sterile gauze pad in his or her left hand and pull the skin superiorly at the upper end of the incision. The taut skin immediately below his or her left hand is cut. As the incision progresses, the gauze is shifted down the incision, always keeping the skin taut such that the knife makes a clean incision. Second, the surgeon may prefer to make the skin taut from side-to-side with his or her forefinger and thumb (Figure 2) as he or she progresses sequentially down the abdomen. Third, the gauze-covered left hand of the surgeon and that of the first assistant may exert lateral tension on the skin, thus permitting the scalpel to create a clean incision. The compressing fingers should be separated and flexed to exert a mild downward and outward pull; however, it is essential that the line of incision not be pulled to one side or the other, i.e., off the true midline. This technique allows the surgeon to have a full view of the operative area as he or she cuts evenly through the taut skin along the length of the incision.

The incision is carried down to the underlying linea alba which may be difficult to find in the obese patient. A most useful technique is for the surgeon and first assistant to apply strong lateral traction to the subcutaneous fat which will then split (Figure 3) directly down to the linea alba. This maneuver may be the only way to find the midline in morbidly obese patients; however, it works equally well in most patients. The linea alba should be freed of fat (Figure 4) for a width of approximately 1 cm such that the margins can be easily identified at the time of closure. Bleeding vessels are clamped carefully with small hemostats and either ligated or cauterized. As soon as hemostasis in the superficial fat layer has been accomplished, moistened large gauze pads are placed in the incision such that the fatty layer is protected from further desiccation or injury. This also aids in providing a clear view of the underlying parietes.

The linea alba is incised in the midline (Figure 5). Pre-peritoneal fat may require division to expose the peritoneum. The surgeon and first assistant alternatively pick up and release the peritoneum to be certain that no viscus is included in their grasp. Using toothed forceps which lift the peritoneum upwards, the surgeon makes a small opening in the side of the tent of elevated peritoneum rather than in its vertex (Figure 6). Usually the tent formation has pulled the peritoneum away from the underlying tissue, and the side opening allows air to enter such that adjacent structures fall away. A culture is taken at this time if abnormal fluid is encountered. Large collections of ascites within the abdomen may be removed by suctioning. The volume of ascites should be recorded, and it may be kept within a special bottle trap if cytologic studies are planned to determine whether it is a malignant ascites.

The edges of the linear alba fascia and the adjacent peritoneum are grasped with Kochers. Care is taken to prevent inclusion and injury to underlying viscera. By continuously elevating the tissues that are to be cut, the surgeon may enlarge the opening with scissors (Figure 7). In cutting the peritoneum and fascia with scissors, it is wise to insert only as much of the blade as can be clearly visualized so as to avoid cutting any internal structures such as bowel that may be adherent to the parietal peritoneum. Tilting the points of the scissors upward may afford a better visualization of the lower blade. Having extended the incision to its uppermost limits, the operator may insert the index and middle fingers of the left hand beneath the peritoneum heading towards the pelvis. The linea alba and peritoneum may be divided with a scalpel (Figure 8) or scissors. Care must be taken in the region of the umbilicus as there are often one or two significant blood vessels in the fatty layer between the fascia and peritoneum. These may be grasped with hemostats and ligated. Additional care must be taken at the extreme lower end of the opening where the bladder comes superiorly. The peritoneal incision must stop just short of the bladder, which is seen and identified as a palpable thickening. In general, the peritoneal incision should not be as long as the facial opening, since undercutting may make the closure difficult. Small incisions may be preferred by the patient; however, an inadequate incision may result in a prolonged and more difficult procedure for the surgeon.